My friend Gladys takes care of her 94-year old mother Sylvia, who has Alzheimer’s. Gladys tries to keep mother up with the world and so was telling her about COVID-19. Sylvia said, “I want that.” Thinking she had misunderstood, Gladys replied, “Oh, no, Ma, it’s a terrible disease that kills old people.” And Sylvia said, “Take me to where they have it.”

Sylvia’s request may sound demented or depressed to you, but it would have seemed normal in previous generations. Back then, pneumonia was called “the old person’s friend.” Before antibiotics and medical supports for breathing, like oxygen and respirators, pneumonia in old people had a death rate of 30–40% or more. When you couldn’t do things, when you were in constant pain, struggling to get through your days, largely isolated from younger people living their lives, pneumonia was your ticket out.

Now, though, the vast majority of people recover from pneumonia, if they have access to medical care and a place to live. Their loved ones don’t have to say goodbye to them, and people often live into their 90s and beyond. Some are happier about this than others.

I was born after the discovery of antibiotics, so I missed the time when pneumonia was usually fatal, but I’m old enough (just turned 70) to remember when death was a normal thing. People were scared of death, of course, but not terrified like they are now, because it was familiar. People weren’t sent away to die in hospitals like cats taken to the vet to be euthanized. They died at home, usually with their family around them, so children grew up knowing that death is real but not horrible.

Now, death is far less real for most of us. Where youth, growth, aging, sickness, and death had been the natural course of life (if you lasted long enough), death is now considered an avoidable and tragic evil.

As a hospital nurse for 25 years, I saw a fair amount of death, and not much of it was good. People died surrounded by strangers, their bodies hooked to invasive tubes and treatments. We medicated them for pain, but we could do nothing to help them make their transition into death. They died alone, unless a nurse or housekeeper had time to hold their hands while they took their last breath.

Yet, many families wanted their deathly-ill relatives to receive all the invasive treatments they could afford. If their doctor tried to get a “Do not resuscitate” (DNR) order, or take them off a mechanical ventilator, families often refused. They wanted “everything” done to keep their loved ones barely alive.

When a society denies death

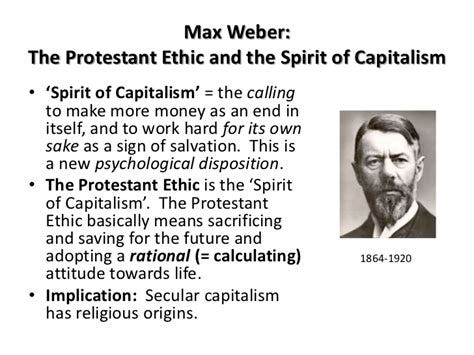

In recent decades, death denial has expanded: we have started to deny aging, too. Because some people can afford to hire caregivers or put their elders in nursing homes, they can move both death and aging out of sight. The shadow side of life falls deeper into the shadows, to the point where society can pretend it doesn’t exist. And then death becomes a terror, the ultimate evil that must be prevented or denied at all costs.

Now, this denial of death and the corresponding terror has spread to every corner of our society. It is shaping our responses to COVID-19 in destructive ways.

In many countries and many American states, a rise in infection rates or in deaths triggers a shutdown of business, education, in-person medical care, social, cultural and religious life. As a result, millions become unemployed, isolated, and impoverished. Of course, rates of infection drop when most people stay home. Then when government tries to reopen things, the numbers go back up, and they close down again. This has happened in my home town of San Francisco three or four times already.

The futility and collateral damage of these policies are obvious and predictable. They aren’t stopping the pandemic; they’re dragging it out, because viruses don’t go away when people hide from them. In the meantime, lives are being lost to isolation, stress, and other effects of the shutdowns. According to diabetes foot expert Jon Bloom MD, the rate of diabetic leg amputations has soared during COVID, because people are afraid to go in for preventative care. Drug overdose deaths are way up.

I do not know why authorities keep ordering these self-defeating policies, but I’m pretty sure people only accept them because they are so afraid of death. Governments know that fearful people will go along with anything, including wars. So, they go to great lengths to tell us we could die if we don’t follow their prescriptions.

If society cannot tolerate the idea of death, then we will never get out of this pandemic. We will keep opening up and shutting down while people get poorer and hungrier. We will wait for deliverance from an effective vaccine that may never come. According to University of Colorado Health, “No vaccine for any corona virus disease has been approved for use with people.” Like many other companies, they are testing one for COVID-19, and making hopeful claims for it, but they have no idea how effective it will be.

What should we do instead?

Full disclosure: I just turned 70 years old and have lived with a disabling illness for over 30 years. I’m one of the vulnerable ones that the lockdowns are supposed to protect. As of November 12, 2020, of the approximately 223,000 “COVID-involved” deaths (about 1 in 1500 people) in the USA, 79% of those who have died were age 65 or older, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

I do not want to be “protected;” I want to live. I refuse to spend my remaining time locked in an apartment, even one with Zoom calls. I insist on living as best I can, and I certainly oppose other people’s lives being stopped to ‘protect’ me.

I’m not saying we should ignore COVID-19. An approach that accepts death would allow for a balanced, sustainable public health response. Everyone could be strongly encouraged to wash hands and faces, to stay home when sick, to wear masks in crowded situations. But they shouldn’t need to stay home when healthy; their workplaces should be open. Cultural events and religious services should resume, though perhaps with some restrictions, as they have in Sweden.

We will do more science to refine our prevention and treatment measures. But the practice of closing down millions of lives to prevent a few, or a few hundred deaths would have to stop.

Unfortunately, that policy would mean accepting that there will still be COVID cases and some deaths, and acceptance of death is no longer thinkable for most people. Just for writing things like this, my progressive public health friends call me a neoliberal who doesn’t care about human life, an ageist who wants to throw old people away. On social media, I read comments that compare riding a bus with driving drunk, or eating at a restaurant with playing Russian roulette. And these writers believe they are ‘following the science.’ They aren’t — they’re believing who they want to believe, panicking in fear of death.

Accept death or deny life

In his book, Staring at the Sun:, Overcoming the Terror of Death, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom MD wrote, “The more un-lived your life, the greater your death anxiety. The more you fail to experience your life fully, the more you will fear death.” Our fear makes us extremely vulnerable to manipulation by promoters of technological promises and pseudo-science.

I believe we will cope with pandemics and other threats if we focus on living and making life better for current and future generations and less on preventing death at all costs. Despite all our medical technology, we can’t live forever and, past a certain level of disability, discomfort and decrepitude, most people don’t want to. We might be scared of death, but that is not the same as loving life.

We need a balance between risk reduction and life maximization. Rather than stopping life to prevent death, it will be much better to enjoy and make the most of the life we have. Yalom’s book gives good ideas on how to get there.

— — — — — —

Thanks for reading! Follow me on Twitter, on Facebook or my medium.com/@davidsperorn Hire me for freelancing, editing, or tutoring on Linked In

Air pollution EU’s #1 health hazard Image: dw.com

Air pollution EU’s #1 health hazard Image: dw.com